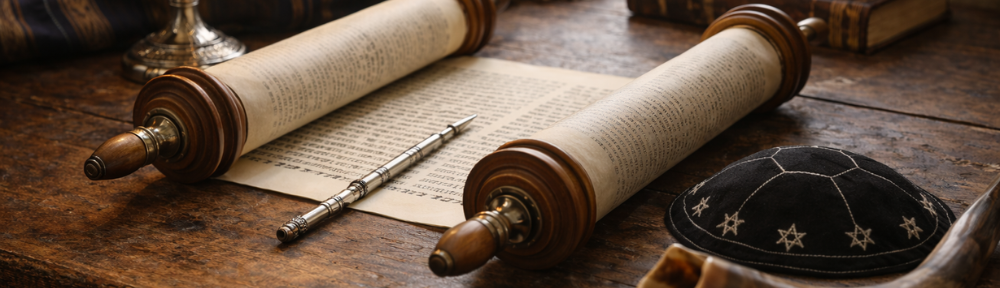

January arrives with a particular weight. It carries fast days, civic memory, and the enduring call to live with conscience. In that spirit, I want to explore how Jewish canonical texts, Torah, Talmud, and their commentaries, shape Jewish thought, behaviour and commemorative events across history and into the present.

It was Rabbi Lord Jonathan Sacks who pointed out that the Hebrew language has no word for “history.” Instead, we have the word zachor, an injunction “to remember.” It is not a suggestion. It is a command.

“Zachor!” as in:

“Zachor” et Amalek asher Korcha b’derech…”

“Remember what Amalek did to you on your journey out of Egypt, how they surprised you on the road and cut off all the weak people at your rear, when you were parched and weary [from the journey], and they did not fear [retribution from] God [for hurting you].” Devarim (Deuteronomy) 25:17

December 30, 2025 (10 Tevet, 5786): One Day, Many Layers

The Tenth of Tevet is known as one of our minor fasts. But what is a “minor” fast? These are fasts and holidays instituted by our Sages, based on their study of the canonized Torah scroll: These events are reviewed and elaborated in the Talmud.

There are four classic minor fasts:

- The Tenth of Tevet (10 Tevet), which commemorates the beginning of the Babylonian siege of Jerusalem during the preiod ot the First Temple.

- The Fast of Esther (13th of Adar), the day before Purim, reminds us of Esther’s request conveyed to Mordechai before she undertook the dangerous initiative of approaching King Ahashuerosh to ask for the annulment of Haman’s genocidal decree against all Jews in all the provinces of Persia: “Go, assemble all the Jews who are present in Shushan and fast on my behalf, and neither eat nor drink for three days, day and night; also I and my maidens will fast in a like manner; then I will go to the king contrary to the law, and if I perish, I perish!” (Ch 4:16 The Book of Esther, The Megillah)

- The Seventeenth of Tammuz (17 Tammuz) is the day the Romans breached the walls of Jerusalem.

- The Fast of Gedaliah (3rd of Tishrei, the day after Rosh Hashanah) commemorates the assassination of Gedaliah, the last Jewish sovereign of Judea after the destruction of the First Temple in Jerusalem.

Clearly, each date has its own story to tell.

And January holds other civic and global milestones that point in the same direction, toward memory, accountability, and the unfinished work of justice.

Martin Luther King (MLK) Day is observed every year on the third Monday of January in the United States, and annually, on January 27, many nations of the world mark International Holocaust Remembrance Day.

All of these occasions offer time and space to remember and reflect on our shared histories.

And January is also the month when we begin reading the Book of Exodus in the weekly Sabbath synagogue service. Every year, it feels newly relevant, this story of an enslaved people freed from the slavery of Egypt by the three siblings, Moses, Aharon, and Miriam.

The Book of Exodus as the Moral and Political Education of a Nation

The first four portions of the Book of Exodus are the most dramatic part of the story. The Israelites had been welcomed into Egypt by an earlier Pharaoh during the lifetime of their brother Joseph who had saved Egypt and much of the civilized world from seven brutal years of famine, but that welcome did not last. and, as the story goes, (Ch 1:8 ) “A new king arose over Egypt, who did not know about Joseph.”

Oppression builds gradually, tightening year by year, until it ends in something horrific: an order to kill all Hebrew baby boys born

We follow the story through the people’s struggle over generations: the birth of Moses, the Jewish baby boy who is raised in Pharaoh’s court by Pharaoh’s daughter; Moses fleeing Egypt as a young man after witnessing injustice and trying to intervene; his marriage to Tzipporah, the daughter of a Midianite prince; and then, later in life, being called by God at the burning bush to return to Egypt, confront Pharaoh, and lead his people out of slavery.

And of course, everyone knows about the epic struggle within Egypt and the Ten Plagues that preceded the Israelites’ marching out of Egypt.

Rabbi Lord Jonathan Sacks explores this story in his book, Covenant and Conversation: A Weekly Reading of the Jewish Bible: Essays on Ethics, and his way of reading the text speaks directly to the world we are living in. These are his themes: Shemot: On Not Obeying Immoral Orders, Vaera: Freewill, Bo: Telling the Story, and Beshallach: The Face of Evil. Just reading those titles, you can already tell these are not light themes for a wintry month.

Shemot: The Quiet Courage of Civil Disobedience

In the first chapter, Shemot, Sacks points to a moment that many people skip: the story of Shifra and Puah, the midwives who were ordered by Pharaoh to kill all Hebrew baby boys as soon as their mothers gave birth.

They simply do not obey.

“Exodus 1:15–1:21:

15 The king of Egypt spoke to the Hebrew midwives, one of whom was named Shiphrah and the other Puah, saying, 16 “When you deliver the Hebrew women, look at the birthstool: if it is a boy, kill him; if it is a girl, let her live.” 17 The midwives, fearing God, did not do as the king of Egypt had told them; they let the boys live. 18 So the king of Egypt summoned the midwives and said to them, “Why have you done this thing, letting the boys live?” 19 The midwives said to Pharaoh, “Because the Hebrew women are not like the Egyptian women: they are vigorous. Before the midwife can come to them, they have given birth.” 20 And God dealt well with the midwives; and the people multiplied and increased greatly. 21 And [God] established households for the midwives, because they feared God.”

There is one line in that passage that always stops me short: “The midwives, fearing God, did not do as the king of Egypt had told them.” (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Shiphrah_and_Puah)

What makes it even more remarkable is how quietly they refuse. No fuss. No drama. Just doing the right thing in the face of imperial power.

“The Midwives Feared God”

The Torah has no word for religion. The closest related concept it offers is what it calls “the fear of God.”

Shifra and Puah apparently believed that God’s moral demands outweighed Pharaoh’s legal demands. And Rabbi Sacks notes that their refusal to follow Pharaoh’s genocidal instructions “may be the first known incident of civil disobedience in history.”

A few verses later, this theme is reversed. Pharaoh commands the Egyptian people to carry out the genocide by throwing all male Jewish babies into the Nile River. The Egyptians apparently feared Pharaoh more than they feared God, and therefore participated in the crime.

Joseph Telushkin compared Shiphrah and Puah’s defection to the rescuers of Jews during the Holocaust. Those who aided and saved Jews were answering to a “Higher Power”; on the other hand, many feared the Nazis’ power more than they feared, or believed in, God’s judgment.”

This principle, refusing to comply with immoral orders, was only formalized in Western law after World War II and the Nuremberg trials, when Nazi officers claimed as their defense, “I was only following orders.” Some orders are so wrong that obeying them makes you responsible, too.

Memory Isn’t Passive: It Demands Something From Us

It would be easy to treat the Exodus story as ancient history. But the Book of Exodus teaches us that overcoming oppression is never simple and leaving Egypt is only the beginning. The harder work is building a moral and just society once you are free. That is the enduring lesson of The Torah, of the five books of Moses seen as a whole.

Martin Luther King Jr.’s legacy is inseparable from contemporary notions of basic civil rights, of nonviolent resistance, and the insistence that when laws are unjust, we cannot simply go along.

For Jews, remembering the Holocaust is never only about the past. It is also about telling the truth in the present, especially when people try to forget it, blur it, or reshape it.

This year, the Jewish community has invited Elisha Wiesel, Elie Wiesel’s son, to preview his recent film about his famous Holocaust survivor father, Elie Wiesel, Soul On fire.

In his 1986 Nobel Peace Prize acceptance speech, Elie Wiesel said the following:

“I have tried to fight those who would forget, because if we forget, we are accomplices…We must always take sides. Neutrality helps the oppressor, never the victim.”

And here too, there is a sentence that lands with particular force: “Neutrality helps the oppressor, never the victim.”

Elisha Wiesel was asked by a reporter:

“What does he think his father would have said about the rise in antisemitism around the world and the drumbeat of Holocaust deniers?”

He replied:

“My father clearly articulated that the antisemites will always hate, even if they mask that hate as anti-Zionism, as though it were somehow separable from antisemitism. My father never failed to stand up for Israel, asserting that only Israelis can best decide how to reach their goals of living in peace in an extremely hostile neighbourhood. And lastly, he insisted that we never relinquish our desire to have a positive impact on the world as a whole. He strongly resisted isolationism as a principle.”

Yes, Holocaust denial continues to plague us. And the more chaotic the world becomes, the more tempting it is for some to adjust history until it is unrecognizable, or to bury their heads in the sand.

Seen from this perspective, the biblical story stops being ancient history. It becomes one of the building blocks of how we understand justice today.

It also reminds me of something we forget too easily: democracy is not only laws and elections. It depends on all of us not leaving our conscience at the door.

This is not a dramatic, cinematic lesson. It is a daily one. Most moral decisions are not made in grand moments. They are made in smaller choices, often in silence, when nobody is applauding.

What do you do when the state commands you to do the wrong thing?

How does a society lose and regain moral freedom?

Why do some people cling to tyranny even when it is destroying them?

What sustains a people across centuries of pressure?

These are some of the questions that Rabbi Sacks addresses in his subsequent essays.

The Question January Leaves Us With

These are some of the reasons that all of these fast days and memorial days matter, not because they keep us stuck in sadness, but because they force us to look clearly at what human beings are capable of. And they ask us, quietly but firmly, whether we are paying attention.

So January becomes one of those months where everything comes together: fasting on the Tenth of Tevet, MLK Day, and International Holocaust Remembrance Day, with warnings from history, all pointing toward the same question:

What do you do with what you know?

Thank you for sharing this moment with me.

I would love to have your feedback.

Footnotes:

- Sacks, Jonathan. Covenant & Conversation: A Weekly Reading of the Jewish Bible: Essays on Ethics. Parashat Shemot.

- Schwartz, Susan. “Son of One of the World’s Most Public Holocaust Survivors Upholds Father’s Legacy.” Montreal Gazette, 21 Jan. 2026.